The Story of a Bridge in Hardy Represents American Infrastructure Issues

by Joe Quinn, AGRF Executive Director

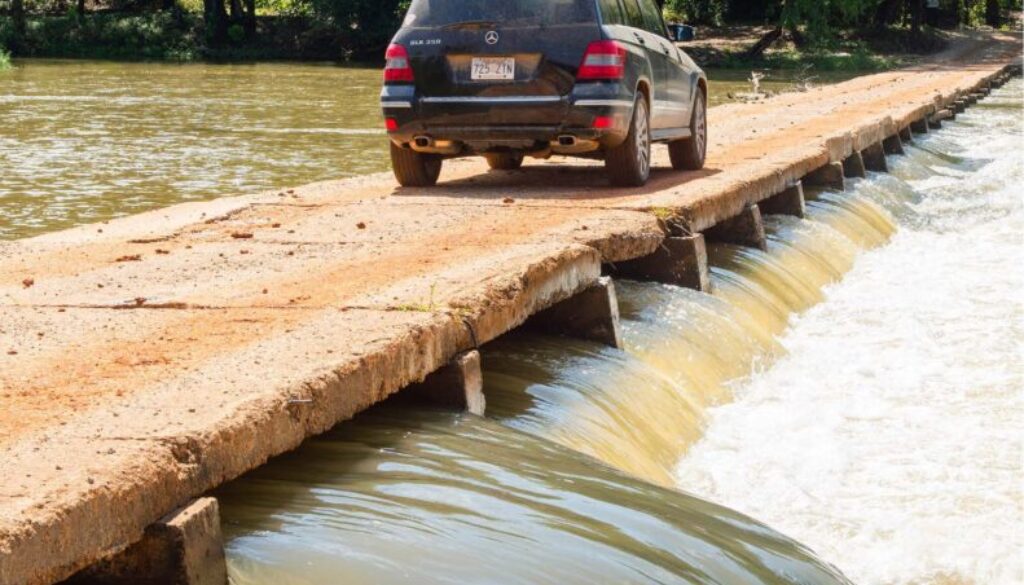

It’s difficult to visualize if you haven’t walked through the mud to stand at the end of the Humphries Ford Bridge in Hardy, Arkansas. The bridge is so low it seems to sit on top of the water. It’s narrow, and there is no guardrail. But despite all of this, until recently, hundreds of cars and trucks have been using the county-owned bridge every week to cross the river. If you had to select just one picture to show what aging infrastructure in Arkansas looks like, this might be it.

On a fall afternoon when the temperature has hit 70 degrees, the bridge looks narrow but passable. But on a spring day after heavy rain when the river is moving fast, it can be treacherous.

Local elected officials as well as sheriff’s deputies and police officers all mention the same thing when talking about the bridge. During periods of heavy rain, the bridge would be partially underwater, yet many drivers would plow ahead anyway. This inevitably led to accidents and calls to 911 to get rescue teams to pull people from the water. Mark Counts is the Sharp County Judge and a former sheriff. He remembers his days in uniform when he says, “I always worried during times when the river was up.”

rkansas Highway Commission Chairman Alec Farmer grew up in nearby Jonesboro. When he was a boy, his mother would come to Hardy with her friends to rock hunt. Farmer remembers that a friend would always drive across the river while his mother closed her eyes. Farmer says, “It was a challenge to cross even in good weather. Driving across the old bridge never got less scary for some of us.”

More than 15 years ago, local county quorum court members commissioned a $10,000 study to investigate the feasibility of replacing the bridge. Quorum Court member Jimmy Marler says, “We had to invest in a study to make sure a new bridge wasn’t doing anything to harm exotic fish.”

Today a larger, brand new, strong-looking Spring River Bridge stands just a few yards from the old mud-covered bridge. The $3.5 million dollar structure will dramatically change local life and driving habits.

It will make it easier for residents and tourists who come to this region in the summer. In Arkansas, tourism is one of the larger sectors of the state economy, and infrastructure that makes it easier for visitors to bring coolers, inner tubes, and dollars to Hardy matters to the local economy.

Residents say the new bridge will be especially welcome on Memorial Day weekend when hundreds of people converge on this area to float the river. On busy days like that, dozens of cars would be backed up with drivers waiting for their turn to navigate the bridge.

Counts says, “Today this new bridge is much safer for travel, and it is also much better for first responders who have had to navigate the narrow bridge for years to get to fires and ambulance calls.”

Hardy is something of a hidden gem in Northeast Arkansas. More than 100 years ago, wealthy families from Memphis came here in the summer to escape the heat in the city. The downtown area feels like a blend of Eureka Springs and Hot Springs in an earlier time. Ice cream shops and diners sit beside antique stores. Along the nearby Spring River are homes that have belonged to the same families for decades.

Barbara Burrow Deuschle lives in Hot Springs where she and her husband Frank own a thriving restaurant. She spent every summer of her childhood in Hardy staying at her grandparents’ home on the river where her mother was raised before moving to Hot Springs. For multiple generations of her large family, Hardy is central to the family story. Grandchildren who work in other states come back at least once a year to decompress with the gentle sound of the river in the background.

Stories are told and retold on the big porch of the 100-year-old family home. On a humid July day there is no air conditioning or cable TV, but there is a sense that this place is something unique. A tourist attraction that has not been overrun with stores selling trinkets and fast food. The family grandchildren bathed in the Spring River while keeping an eye open for snakes.

Deuschle says, “The Spring River is unique. It means everything to people who understand Hardy and who have spent time in the cool water on a hot summer day. I don’t think there is any community in Arkansas where a river is more central to life than what the Spring River means to Hardy.”

While the river is a major part of life here, the Humphries Ford Bridge has always been a part of navigating over and across the river. Bridges in towns like this are a lifeline, and everyone has a story of trying to drive across this low water bridge when the water is rising, but most residents also understand the area has long needed something larger and safer. No one knew that more than the ARDOT engineers who helped the county design and build a structure that was overdue.

Lorie Tudor says, “The bridge was functionally obsolete. ARDOT is able to put aside federal funding for projects like building this new bridge. Our engineers can assist the local community with designing the new bridge, letting out the bids for the work that needs to be done, and getting the permits communities needed to move ahead with the construction.”

The reality facing Tudor and her team is that eroded and old bridges in rural Arkansas communities are not unusual. While ARDOT provided the expertise to build the new bridge, it is owned now by Fulton County, and the county will have to manage the maintenance and upkeep. Sharp County Judge Mark Counts says, “The synergy between ARDOT and the construction companies who did the work on the bridge has been incredible.”

In some ways, Tudor is responsible for a culture change that makes projects like this easier to accomplish. There was a time when contractors and ARDOT had a somewhat adversarial approach, but Tudor has made it her practice to listen closely to what contractors need and address their challenges. That cooperation makes life easier for local leaders like Judge Counts. It also means that getting from Hardy to Cherokee Village is safe now.

At a recent dedication of the new bridge, Tudor told the crowd, “We need to celebrate these projects that show where your tax dollars are being spent.” Under Tudor’s leadership, ARDOT has been aggressively working to tell road stories in a different way. The department talks in terms of how multiple projects have changed a region, instead of just discussing one ribbon cutting at a time. Going into detail on how a project like the Spring River Bridge became reality is a priority for the ARDOT communication team, not an afterthought.

The new bridge means safer and more convenient travel, but it also means a lot to emergency vehicles, both in terms of how they get to the scene of 911 calls, and how often they have been called out to help people who have encountered problems while crossing the bridge. State Representative Bart Schulz represents a district north of Cave City. He also owns an ambulance service. Schulz says, “This is a tremendous step for the region in terms of safety. In some cases, the new bridge will reduce emergency response time to patients by as much as 45 minutes. But this is not an isolated situation, there are a lot of bridges in rural Arkansas just like this.”

In the 15 years that local leaders have worked on replacing the bridge, six different county judges have been involved in the discussion and planning. It took some time to get to the dedication of the new Spring River Bridge, but few roadway projects in Arkansas have probably ever had as immediate and significant an impact on a region as this new bridge has had. ARDOT District 5 Engineer Bruce Street says, “This is the biggest improvement I have witnessed in my DOT career. Going from a low water bridge to the impressive structure being built now will have a big impact on the communities to the west that depend on crossing the Spring River to get to Hardy.”

At times, the discussion about improving American infrastructure can seem abstract. It’s a dialogue with dollar figures so large they can be difficult to comprehend. Thousands of aging roads and bridges across the country need to be replaced. But standing on the banks of the Spring River on a perfect fall day, the larger infrastructure dialogue can come into crystal clear focus looking at one $3.5 million dollar project that has changed life for one river town and the counties around it.